Albert Einstein, Ted Chiang, and the physics of time travel (podcast)

Modern physics shows that it’s possible to manipulate time. But does that mean we can travel to the past? And what does this say about what time actually is. Is the future real? Is the past? Do other points in time exist in the same sense that the present does?

In this second episode of the Monitor’s six-part series, “It’s About Time,” hosts Rebecca Asoulin and Eoin O’Carroll talk to a physicist, a philosopher, and a novelist who have all made it their life’s work to answer the question: What is time?

The physicist – Ron Mallett – designed a real (theoretical) time machine based on Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity. According to Einstein, time isn’t a rigid, invariant backdrop. Instead, it can be stretched, warped, and perhaps even curved into a closed loop where an object traveling through it ends up just where – and when – it began.

Einstein’s work inspired Dr. Mallett, whose career in theoretical physics was sparked by the death of his father when he was 10. “I thought, if I understand Einstein, I can understand how to build a time machine,” Dr. Mallet says. “I can go back and see him again.”

Of course, time travel is still firmly in the realm of science fiction. So Rebecca and Eoin turn to sci-fi writer Ted Chiang, who wrote the short story that was the basis of the 2016 film “Arrival.” He says thinking about time travel can help us make meaning out of the trajectories of our lives.

“Time travel stories have the potential to help us reconcile ourselves with our past,” Mr. Chiang says. “Because while we cannot change the things that happened to us; we cannot change the decisions that we made; we can potentially change our relationship to the past.”

This is Episode 2 of “It’s About Time,” our six-part series that’s part of the Monitor’s “Rethinking the News” podcast. To listen to the other episodes on our site or on your favorite podcast player, please visit the “It’s About Time” series page.

This story was designed to be heard. We strongly encourage you to experience it with your ears, but we understand that is not an option for everybody. You can find the audio player above. For those who are unable to listen, we have provided a transcript of the story below.

AUDIO TRANSCRIPT

Jessica Mendoza: Welcome to “Rethinking the News” by The Christian Science Monitor. I’m Jessica Mendoza, one of the producers. Today, we’re releasing the second episode in our new six-part science series, “It’s About Time,” hosted by Rebecca Asoulin and Eoin O’Carroll. If you haven’t listened to our 1st episode, check it out! OK, let’s get started.

[Music]

[Montage of clips from different interviews]

Rebecca Asoulin: So the question that we ask everybody: what is your definition of time?

Tim Wilson: Oh, gosh, that’s a big question. Ummm….

Dawna Ballard: I absolutely cannot define time. Because time is really so many things, there’s not just one time.

Dorsa Amir: (sighs) What is time, really? Ummm….

Tyson Yunkaporta: I don’t … (sighs) I don’t really have one.

Leah Ruppanner: So the – I would define time… OK, I’ll start again.

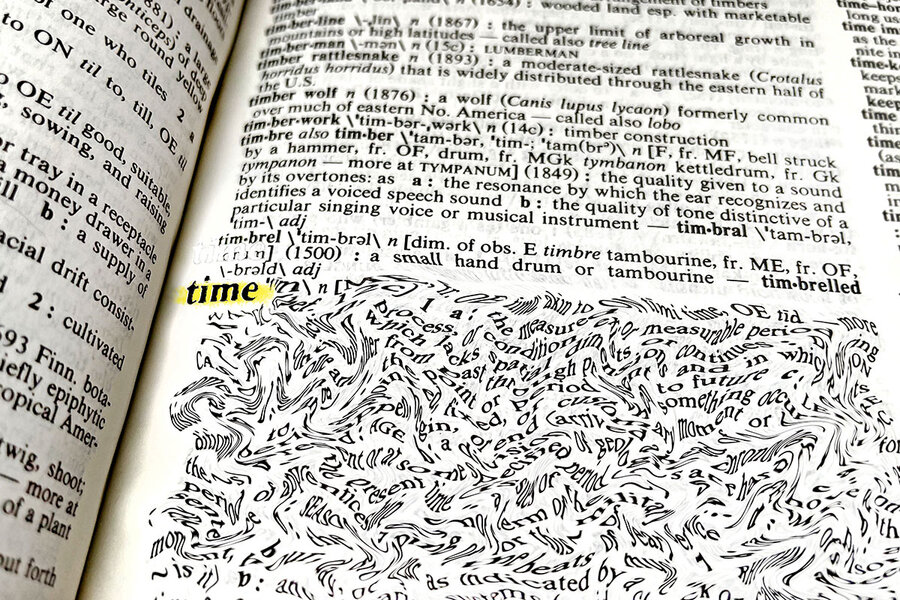

Dorsa: I’m really stumped. I don’t know if I have a definition for you. I kind of want to look up Merriam Webster and just pretend that was my definition.

Rebecca: This is “It’s About Time.” A series all about…

Eoin O’Carroll: Time. I’m Eoin O’Carroll.

Rebecca: And I’m Rebecca Asoulin.

Eoin: In this science series, we interview experts on time. They’ll help us unravel its mysteries.

Rebecca: Because understanding time more deeply can help us make the most of the time we have.

[Music]

Rebecca: So what is time?

Eoin: According to Oxford University Press, “time” is the most common noun in the English language. We use it all the time. Yet we find it so hard to define.

Rebecca: We spoke to a lot of time experts for this series. And we asked every one of them to define time for us. They all struggled. And when they did finally define it, their definitions were really different.

Heather Dyke: It’s so fundamental that most of the time people don’t think about it, you know? But it’s always there in the background.

Eoin: That’s Heather Dyke, a philosopher of time. What she’s saying is: Time is hard to define because it’s just sort of there. It’s such a slippery concept.

Rebecca: This episode is about diving deep into that concept. We’ll talk to a philosopher, a physicist, and a novelist who have all made it their life’s work to answer the question: what is time? And maybe by trying to figure out what time is and how it works, we can learn a little about how to reframe the challenges in our own lives.

[Music]

Rebecca: So I’ve personally always found philosophy kind of baffling. It just never seemed that useful to me in terms of people’s day-to-day lives.

Eoin: I mean, philosophy is aimed at the most baffling questions. The ones that can’t be settled by normal science. So if you’re not baffled on some level, I think you’re not doing it right.

Rebecca: Comforting, very comforting, Eoin.

Eoin: But, you know, I think philosophy’s also unavoidable.

Heather Dyke: So as humans, we’re sort of natural philosophers. We want to understand the world. But there are so many different aspects to our understanding of the world in general, but I think this is particularly true of time.

Rebecca: This is Heather Dyke again. She’s a philosopher of time at the University of Otago, in Dunedin New Zealand. Heather says her goal as a philosopher is to understand time in itself. And how time connects to all different parts of our lives – from the politics of time, to the psychology of time.

Eoin: Heather’s understanding of time as a philosopher helped her put into perspective a difficult personal decision.

Rebecca: That decision centered around an 18th century manor house in the English countryside.

Heather Dyke: Well, it was built by my ancestors in the 1730s. Three stories. Big blocks of sandstone, arched windows. It had beautiful gardens.

Rebecca: Just what you’d expect if you watch any BBC drama.

Heather Dyke: It was full of old, you know, family portraits. And my great grandfather, he was massively into his big game hunting. So we actually had an elephant’s foot that had been made into a whiskey decanter holder. You know, it was really like a kind of, an old stately home that you’d go and visit.

Rebecca: Heather moved to the house when she was 12. And she used to visit it before then.

Heather Dyke: It’s a vast place, but they didn’t have spare bedrooms for us. So we camped in the garden.

Rebecca: By 2012, Heather has moved to New Zealand, and lives with her husband and children. And she realizes that she needs to make a decision, because 300 years really does a number on a place. Should they try to save the house or sell it?

Heather Dyke: My parents were getting elderly and it was kind of crumbling. You know, it had a leaky roof and it had chimneys that were falling down, windows that were falling out.

Rebecca: Heather decides she wants to try to turn it around which would mean making enough money to keep up the maintenance of the house. So she moves with her family from New Zealand back to England. And they try to make it work. But after seven years of trying, it becomes obvious that the house can’t be saved.

Heather Dyke: Nobody ever wants to be the generation that gives up and sells up. But there really was no other option. The last Moreland, which was my maiden name – the last Moreland to make any money died in 1784. That just made me think, “We’re not doing the wrong thing here. We’re doing the right thing. It should have been done a while ago.”

[Music]

Rebecca: You might be thinking: what does any of this have to do with time? The decision felt like the right thing to do. But it was still really painful. And her philosophy on time actually helped her come to terms with what happened.

Heather subscribes to a philosophical theory of time called the B theory.

Heather Dyke: The B theory says that time is a little bit like space, in that the moment that we designate as “now” is no more real than any other moment.

Rebecca: What she’s saying is all times exist, regardless of whether we’re perceiving it or not. So Eoin chatting with me right now in 2021 is as real as Eoin back in let’s say, 1990.

Heather Dyke: I treat “now” a little bit like we treat the notion of “here.” You know, I’m here in Dunedin. You’re over there in, I don’t even know what city you’re in.

Rebecca: California.

Heather Dyke: California. There you go. Thank you. But I don’t think that California is any less real than Dunedin just because it’s not here. Right? And so. So that’s kind of analogous to how the B theorist thinks about “now.” I don’t think that 1733 or 2120 are any less real than this moment now. I just think that they’re located at different times, just like California is located at a different place from me.

Rebecca: In the B theory, there is no present moment. We label things “past,” “present,” and “future” to match up with our perception of the world. But what we consider the present isn’t special in this theory. I know this is mind blowing. It’s really counterintuitive to our experience.

But Heather says it’s how time really works. And the theory is really comforting to her. So back to the manor house.

Rebecca: So in the B theory, is it that you were always going to sell the house?

Heather Dyke: So, no, that’s not – that’s not true. Because… so it is tricky to get your head around this. So just because the time is real, the future time is real, doesn’t mean that what happens at that time happens of necessity. It happens because of the things that happened before it. And those things can include free choices.

So take me back to 2012, when we first went there. It wasn’t then fixed that we would sell in 2019. That came about because of the various choices and decisions and other external factors. Things might have gone differently, but as it turns out, they didn’t.

Rebecca: For Heather, when something bad happens, it’s comforting for her to know that our decisions, aren’t the only reason things turned out the way they did. To her, the future is not totally limitless. Whether or not the theory is true, it resonates with Heather and helped her deal with the pain of selling her family’s house.

Heather Dyke: So I now can look back on that as a kind of finite closed – like it was a return journey. Do you know what I mean? Whereas on the way there, it felt like an open future. And I think my B theoretic view of time, it sort of helps me with that, because I don’t think the future is this kind of open realm. I do think that we are able to affect the future and our choices and decisions matter. They have causal influence, but I don’t think of it as this kind of open realm of possibility. I think that helps in cases when things don’t go as planned.

[Music]

Rebecca: The B theory’s foundation is built off of physics. In particular, Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity. Physics is foundational to many understandings of time.

Eoin: Time – if it really exists – is a characteristic of the physical universe. So if we’re going to find out what time really is, it makes sense to ask a physicist.

[Music]

Ron Mallett: I thought, “If I understand Einstein, I can understand how to build a time machine.”

Eoin: That’s physicist Ron Mallett. He became a physicist because he wanted to build a time machine. Yes you heard that right. And he succeeded, kind of. He says he actually came up with a design for a real time machine. Well, a real hypothetical time machine, with real science. And lasers!

Rebecca: A childhood tragedy led to Dr. Mallett’s desire to do that.

Ron Mallett: My father was a television repairman. And I idolized him. I mean for me, the sun rose and set on him. He was just everything for me.

Eoin: Growing up, Dr. Mallett’s dad would give him scientific toys, and he inspired his love of reading. Then when Dr. Mallett was 10, his father –

Ron Mallett: – died of a massive heart attack. Suddenly, when he was only 33 years old. And it completely devastated my world. I went into a black hole.

Eoin: His father’s death plunged the family into poverty. His mom was now a single Black mother, in 1955, with four children to raise.

Ron Mallett: A year after he died, I came across the book that changed my life. It was H.G. Wells’ “The Time Machine.”

Eoin: “The Time Machine” was written in 1895. It tells a story of a man who travels hundreds of thousands of years into the future.

Ron Mallett: At the beginning of it, it said that: “Scientific people know very well that time is just a kind of space.” And we can move forward and backward in time, just as we can in space.

Eoin: This quote is from the Time Traveler, the book’s main character. It’s part of his explanation of how his time machine works, which treats time as though it were a fourth spatial dimension.

Ron Mallett: And when I read those words, I thought, “Oh, this is it. This is the thing that is going to allow me to see my father again. If I could build a time machine, I can go back and see him again.” My mother had kept these all television and radio parts of my father … and I even tried to put something together that looked like the illustration. I mean, with bicycle parts in this thing. And of course, nothing worked.

Eoin: After all, Dr. Mallett was 10 years old at the time. But that first failure didn’t stop him. A few years later, he found another book at the Salvation Army.

Ron Mallett: It was a paperback that had Einstein on the cover of it, standing next to an hourglass.

Eoin: That book was called “The Universe and Doctor Einstein.”

Ron Mallett: – and so I got the paperback and I didn’t understand most of it. But I did pick up the essence that Einstein said that there are ways you can alter time.

[Music]

Eoin: And so Dr. Mallett becomes a theoretical physicist specializing in Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, using it to create a theoretical time machine. He says he showed that it’s mathematically possible to use lasers to bend time back on itself.

To understand how Dr. Mallett does that, we first need to talk about Einstein and his theory of relativity – there are actually sort of two theories, really. Einstein’s work is the basis of Dr. Mallett’s real hypothetical time machine.

Rebecca: It’s also the foundation of physicists’ modern understanding of how time works.

Eoin: First, we’ll talk about Einstein’s special theory of relativity.

[Music]

Ron Mallett: Suppose that you’ re standing in front of a vehicle and a friend who’ s moving in the vehicle throws something at you.

Eoin: Let’s say the vehicle is going at 60 miles an hour, and the ball that your friend is throwing is going at 10 miles an hour.

Ron Mallett: Well, if you’ re standing outside the vehicle, the object isn’ t going to be coming at you at 10 miles an hour. It’ s going to be coming in at you with the speed of the ball plus the speed of the vehicle.

Eoin: If you’re in the car, the ball is going 10 miles an hour. But if you’re standing outside the car, you’ll see that ball coming at you at 70 miles an hour. In other words, how fast something moves depends on your frame of reference.

But, by the beginning of the 20th century, physicists had hit a stumbling block. This principle did not apply to light. Light seemed to travel at the same speed, regardless of how fast the observer was moving.

Rebecca: And that’s weird. Because everything else changes depending on your frame of reference. And so –

Ron Mallett: – what Einstein said is that the only way that the speed of light could be the same, no matter how fast the source of light could be, is that something else has to be changing. Space has to be changing and time has to be changing. Time has to be slowing down so that the speed of light can stay the same.

Rebecca: And that is the Special Theory of Relativity.

Eoin: This was totally revolutionary. It created a whole new world for physicists to explore. Before this, everyone thought time was absolute. Now they understood it was actually relative. (Hence, relativity!) Special relativity became the basis for Einstein’s theory of gravitation, which he called general relativity.

Ron Mallett: The special theory says that time is affected by speed. The general theory says time is affected by gravity.

Rebecca: The general theory was what Dr. Mallett based his time machine math on.

This stuff is complicated. Dr. Mallett has spent his entire career on this topic. Einstein spent years developing the theory. It just takes some time to absorb.

Eoin: Einstein’s basic idea was that gravity bends space and time.

Ron Mallett: If gravity can affect time and light can produce gravity, then light can affect time. That was my breakthrough, by realizing that light can alter time.

Eoin: Dr. Mallett proved mathematically that by using a beam of laser light –

Ron Mallett: – it would be possible to twist space and to eventually twist time into a loop. And along that loop, in time, it might be possible to travel back into the past.

Eoin: Like we said, a real hypothetical time machine. (As in the hypothesis is real! And the math plays out.) But he hasn’t actually been able to build it. It’s too expensive. It could cost billions of dollars in the end.

Rebecca: And instead of finding this infuriating, Dr. Mallett is … pleased.

Ron Mallett: For me, the satisfaction is that I actually have achieved the goal that I had, of finding out a way that a time machine could possibly be built based on Einstein’s work. Unfortunately, it won’t allow me to go back to see my father – yet.

[Music]

Eoin: So what is a time from a physics standpoint? Time is malleable. Before Einstein, time and space were absolute. But Einstein showed us that the real absolute in our universe is not time or space, it’s the speed of light.

Einstein’s theories give us all kinds of new physics and new technologies like GPS, nuclear power, and even those old cathode-ray televisions.

Rebecca: They haven’t yet gotten us back to the past. But Einstein’s theories still open up a whole universe of ideas for all sorts of thinkers. In fact, physics is the starting point for this episode’s third and final story.

[Music]

Rebecca: I really wanted to talk to a science fiction writer about time. In science fiction, you can kind of hand wave the mechanics of time travel. It doesn’t need to be possible. You don’t need to fully know how time travel would work to explore all of its juicy dramatic consequences.

Eoin: Still, science fiction writers often know and incorporate a lot of physics into their stories. Even if a lot of that is left off the page.

Rebecca: But in a sci-fi story, the answer to the question: what is time? Is ultimately whatever the author wants it to be.

Ted Chiang: Time travel is kind of a literalization of memory. When we think about the past, we are metaphorically traveling back in time.

Rebecca: That’s Ted Chiang He wrote the short story that the 2016 film “Arrival” is based on. It’s called “Story of Your Life.”

Both the film and the story are about a linguist who is trying to make sense of an alien language. Through that work, she begins to understand time as the aliens do. She can remember her future as well as her past.

Ted has written two collections of short stories. The second collection includes the time travel story, “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate.” In a lot of his work, characters try to come to terms with their pasts.

Ted Chiang: Time travel stories are about how we feel about our past. They can offer a kind of wish fulfillment, you know, giving us an opportunity to make decisions differently.

Rebecca: And most of the time, these stories –

Ted Chiang: – are about regret, about events in our past, decisions we made that we wish we had made differently.

Rebecca: “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate” is about a fabric merchant in medieval Baghdad. He meets a shop owner who has a time travel portal. The shop owner tells him about three others who have used the portal before the merchant decides whether or not to use it himself.

In the story, Ted’s rules of time travel are based on physicist Kip Thorne’s wormhole version of time travel which obeys Einstein’s theory of relativity. According to Kip Thorne, even if we could time travel, we can’t change the past.

But the vast majority of time travel fiction is about people going back and changing their past. Ted is OK with stories like that –

Ted Chiang: – mainly because I think that they are trying to convey a positive message. They are trying to tell people that you have agency, that you can change your life, you can make a difference. I think those are good things for a story to do. But in reality, we cannot go back and do things differently.

Rebecca: Ted found himself wanting to write fiction that took that less popular route.

Ted Chiang: I think people don’t want time travel stories in which you cannot change the past. We usually find them depressing. They are usually couched as tragedies. So one of the things that I was trying to do with “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate” was to write a story about time travel in which you could not change the past, but where that was not a tragedy.

Rebecca: In his story, the fabric merchant had experienced a loss 20 years before that left him hollow. He felt like he couldn’t atone for his past mistakes.

I’m not going to spoil the story, so all I’ll say is it ends with this powerful line: “Nothing erases the past. There is repentance, there is atonement, and there is forgiveness. That is all, but that is enough.”

[Music]

Ted Chiang: Time travel stories have the potential to help us reconcile ourselves with our past. Because while we cannot change the things that happened to us, we cannot change the decisions that we made, we can potentially change how we feel about what happened to us.

I’d like to see more stories in which time travel is used as a way of recognizing that even if you cannot change the past, you can change your relationship to the past. You can grow and learn.

[Music]

Rebecca: Sci-fi writer Ted Chiang, philosopher Heather Dyke, and physicist Ron Mallett, all explored different aspects of time. We need to look at different perspectives, because time touches every part of existence. Shifting our perspective on time can also help us make the best of the time we have.

Eoin: So Rebecca, what’s your definition of time?

Rebecca: I think time doesn’t have a neat definition. It really depends on the context. And I think back to all our interviews, and I realize why both of us always prefaced the question, “How do you define time?” by saying that it was a really unfair question. It’s so hard to define.

Eoin: It’s almost like the more we use a word the harder it is to define. And we use the word “time” all the time.

Rebecca: Do you have a definition?

Eoin: Before we started this series, I came up with what I thought was a pretty good definition of time. Time, I thought, is the “perceived dimension of reality along which change occurs.”

Rebecca: What do you think now?

Eoin: Now, I think I have a better definition. Time is this:

[Long pause]

Rebecca: So time is silence?

Eoin: Not necessarily silence — it’s the thing that you’re experiencing as you experience silence. [very long pause round 2]

[Music]

Rebecca: Thanks for listening! We hope you feel inspired to read or watch a good time travel story. Don’t forget to subscribe to “Rethinking the News” wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating or comment.

Eoin: And share this series with your friends, family, and coworkers! You can find us at csmonitor dot com slash time!

Rebecca: This series is hosted and produced by me, Rebecca Asoulin. My co-host is Eoin O’Carroll. It was produced with Jessica Mendoza. Editing by Samantha Laine Perfas, Clay Collins, and Noelle Swan. Sound design by Noel Flatt and Morgan Anderson. With production support from Ibrahim Onafeko.

This story was produced by The Christian Science Monitor, copyright 2021.

[End]