Arakawa & Gins’s Masterpiece Has Sold

Photo: Courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

Eternal life has fueled many fantasies, but for the artist Arakawa and the poet Madeline Gins, it was doctrine. “It’s immoral that people have to die,” Gins once said. The couple had but one mission in life: to fight death through their art. “If you change your environment, you can change yourself,” Gins said in a 2011 interview. The architect-artist couple Arakawa & Gins insisted that constantly testing your senses and perception, and using every muscle in your body, would stimulate your immune system. So they built spaces — like rainbow-colored lofts in Tokyo in which the floors are bumpy, the light switches are all at different heights, and the walls are different textures — that literally and figuratively keep you on your toes, guessing at what’s around the corner, keeping your mind alert. Regular houses reminded Arakawa & Gins, they said, of coffins: predictable, boredom-inspiring, and therefore murderous.

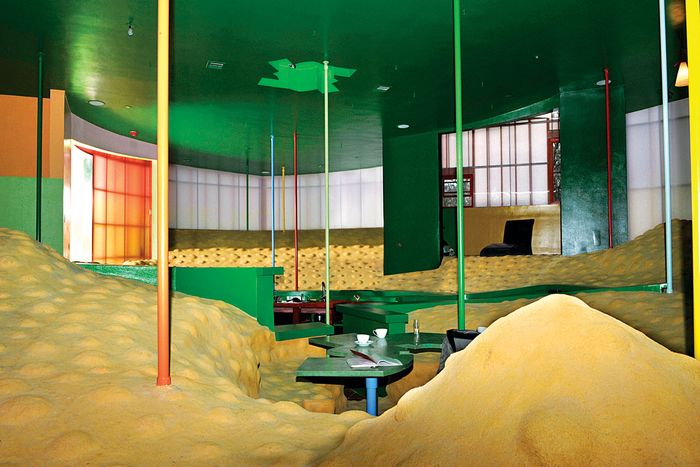

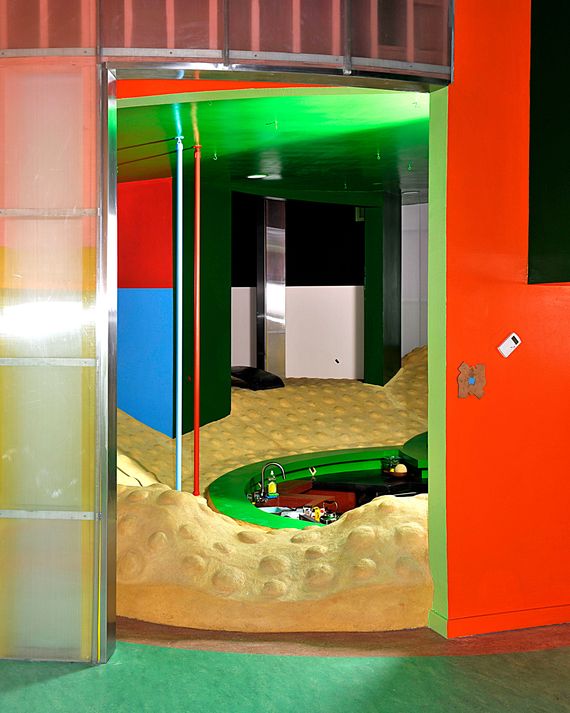

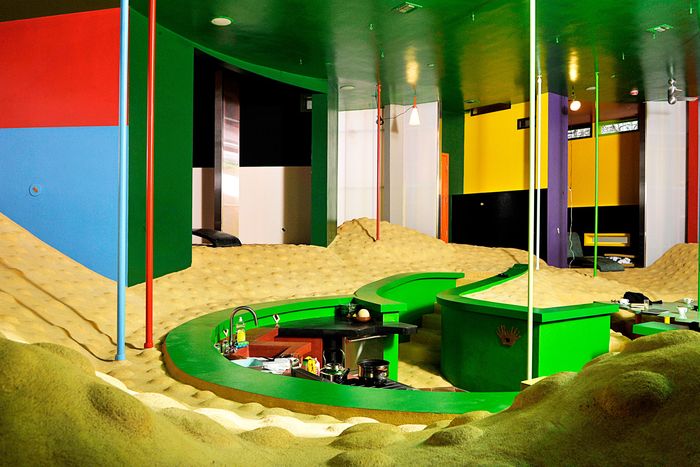

They published books about their theory of “reversible destiny” and conceived designs, like the 2003 idea to build a utopian megastructure on Tokyo Bay and 2011’s “Healing Fun House” project. But, of course, such audacious ideas were easier to explore on paper than in the real world. They built only five projects: the aforementioned Tokyo lofts; the Site of Reversible Destiny theme park in the mountains outside Nagoya; an installation at the Nagi Museum of Contemporary Art, near Okayama; a sculptural staircase at Dover Street Market in Murray Hill; and the Bioscleave House (Lifespan Extending Villa), completed in East Hampton in 2008, which they thought of as the fullest and richest example of their thinking. It was the subject of magazine stories and had a following among architects and designers.

Photo: Courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

And it is, at least to those who get it, a beautiful place. “It feels like you’re stepping out of the world and into a different sphere,” says New York’s Amelia Schonbek, the author of the Awl’s 2016 profile of Gins. “The light filters in through these colored, translucent windows and the house was acoustically designed so that when it moves, it creaks in this sort of otherworldly way.” JB D’Santos — the real-estate agent with Brown Harris Stevens who has represented the house since 2018 as it has gone on and off the market — is an enthusiastic fan, and not just because he is tasked with selling the place. Down to the lumpy floor, in fact. “I take my shoes off, walk over the mounds, and feel rejuvenated,” he says. “The house is all about experimenting with the human mind, to get you to move out of your comfort zone.”

The real-estate saga surrounding the Bioscleave House is inseparable from questions about what it even is: A collectible work of art, a private home that happens to come with access to a private beach, an architectural theory manifested in three dimensions, a covetable slice of East End land? “Oh no, it’s the Bioscleave House again,” a recent story on a Hamptons real-estate blog announced when it went back on the market this spring for $975,000 — a fire sale compared to the house’s asking price of $5.5 million in 2009. Rumors circulated that if the house couldn’t find an appreciative buyer, it would face the wreckers; developers saw more value in the one-acre site than in the bizarre building on it. A house meant to fortify eternal life was itself on the brink of death. It doesn’t seem like anyone has really lived there aside from short stays focused on experiencing the novelty of such a strange place. It was unlivable — and unsalable — as a house and existed as a precious (though not that precious, judging by the final price) art object, which is finally how it sold this summer.

Photo: Courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

Photo: Courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

The Bioscleave House was commissioned in 1998 by Angela Gallman, an Italian art collector who was friends with Arakawa & Gins. Its name was inspired by the twin opposing definitions of the word cleave: to join, but also to separate. It is painted in 52 different colors and has no doors inside, and the floors, as in other Arakawa & Gins projects, are bumpy and uneven. Two bedrooms, a study, and a bathroom radiate from the main living space, centered on the sunken kitchen. There are poles around the hilly living space so people can grab them if they lose their balance.

Even with a client who understood the reversible-destiny theory, and appreciated it enough to take a risk on realizing it, the house was always fraught. Gallman had trouble finding contractors to build the place, and Arakawa & Gins simplified the plans in response. Technically an addition to a Carl Koch Techbuilt prefab from the 1960s, the 2,700-square-foot house took longer and cost more (as most custom homes do) than Gallman expected. She stopped construction in 2007 and put the house — still a shell after nearly a decade — on the market. Before it was even finished, the threat of demolition loomed. Then Professors Group, an anonymous newly formed LLC, bought it from Gallman for $1.5 million and spent another $1 million to finish the project over the next year. “After this, Gehry, Rem Koolhaas are boring,” Gins crowed to the New York Times soon after their magnum opus was finished. “We should win a Nobel Prize for this,” Arakawa chimed in.

Photo: Courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

The project did not confer eternal life on either of its makers. Soon after finishing Bioscleave, Arakawa began to show symptoms of ALS, and he died in 2010 at 73. The house went on the market afterward, with its price reduced to $4 million. Gins continued to develop the reversible-destiny concept, including a “healing center” for a client in Greece, who died before construction began. Soon after, Rei Kawakubo commissioned her to build the staircase at Dover Street Market, which Gins called the “Biotopological Scale-Juggling Escalator,” and she incorporated scale models of Bioscleave’s bedrooms and bathroom. Gins, who had been diagnosed with cancer in the aughts, fell ill while working on the project and died in 2014, shortly after the store opened. Schonbek got to visit the house six months later, unaccompanied, and Gins’s dirty laundry remained in the bedroom, her medicines on the kitchen counter.

Since the Professors Group LLC has owned the house (located at 113 Springy Banks Road), it has been used as a residence, an artist’s studio, and a site for research into how design affects bodies. A number of architects visited the house in order to experience it firsthand and write about it. For a time, Professors Group also hosted the Bioscleave Lab, a salon of sorts that sought to “help protect and preserve our shrinking environment, and to work on finding solutions to pressing global issues such as justice, civil rights and world peace,” according to its website. (Andrew MacNair, an architect, is listed as the Lab’s director and is one name associated with the LLC.) Photos on the site showed the Bioscleave House transformed into a recording studio of sorts.

But “there comes a time in life where you have to depart from things,” D’Santos says about the sellers’ decision to put the Bioscleave House on the market three years ago. He’s discreet about the sellers’ identity and wouldn’t say who they were, except that they are a retired professor and his wife who live in Manhattan. He mentioned only that they often spend weekends at the house and entertain guests there and that there aren’t any photos of the prefab section of the house in listings because it is used as an artist’s studio. “They had it for many years but decided to part from it,” D’Santos says. “Their daughter is in college, and so their priorities changed. And they are focused on other things.”

Photo: Courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

Photo: Courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

When the house went on the market in July 2018 for $2.495 million, it received a healthy amount of publicity. Concerns about its future also surfaced. The Architect’s Newspaper once again raised fears of demolition. At the time, the owners were said to be working with Professors Group on various preservation plans that involved finding investors to help fund the home’s maintenance (and tax bill, presumably), exploring what it would take to disassemble the house and move it to a nearby public venue like the Parrish Art Museum or LongHouse Reserve, or finding a private buyer who was eager to preserve it.

There weren’t any serious offers — from developers, private buyers, or institutions.

According to D’Santos, an actor from the Netherlands wanted to buy the place and turn it into a study house and research center. However, he and his partner had a second child and decided it would be too much to take on a project like this. After only six months on the market, Bioscleave was relisted for $1.495 million in early 2019. After the price drop, another actor, this time one based in Los Angeles, came to the house and even had an inspector visit. It didn’t go any further. “I kept hearing, ‘I’ll have an offer, I’ll have an offer,’ but they took too long,” D’Santos says. “Nobody Wants This Bizarre House That’s Supposed to Extend Your Life,” the New York Post jabbed in a headline for a 2019 story after the price dropped again to $1.29 million. The sellers took the house off the market soon after.

The house’s listing in 2018 coincided with a time of rediscovery of Arakawa & Gins within the arts and architecture communities. In the spring of 2018, Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation held an exhibition on the couple’s work. Publications like Metropolis, PIN-UP, and Wallpaper covered the show and nodded to the scarceness of built work from the duo, including Bioscleave. The New York Public Library also hosted a talk by a filmmaker who produced a documentary about the house. “The House of Our Dreams Is for Sale in East Hampton, New York,” Architectural Digest reported in February 2019. Gagosian also held an exhibition of Arakawa’s drawings and published a lengthy story on his and Gins’s work in its quarterly magazine.

Photo: Courtesy of Brown Harris Stevens

Implausibly, there’s one other significant character in this story: Bernie Madoff. In 2008, less than a year after Bioscleave was finished, Arakawa & Gins lost their life savings — supposedly $20 million invested with Madoff — and were scrambling to protect whatever assets they had left. According to court records, just before the scandal broke, Arakawa & Gins withdrew over $11 million from their Madoff-managed accounts, $7.5 million of which was other people’s money, according to Irving Picard, the court-appointed trustee handling the recovery of funds in the Madoff case. Picard was targeting Madoff clients who withdrew money from their Madoff accounts around the time the Ponzi scheme was revealed, the Architectural Body Research Foundation, Arakawa & Gins’s office, being one of them. The couple subsequently laid off all but one employee — Johanna Post, a longtime project manager who is also the wife of the Professors Group’s Andrew MacNair — and tried, unsuccessfully, to sell one of their most famous works, The Mechanism of Meaning, a series of 83 large-scale paintings, for $17 million to a museum or an institution. They also opened a new nonprofit organization, the Reversible Destiny Foundation, as a way to protect their work from the Madoff fallout.

The legal problems continued well after Arakawa & Gins’s deaths. People in their circle and in charge of their estates disagreed on what to do with their body of work. The RDF leadership was uninterested in Bioscleave and cared more about selling Arakawa’s paintings. Gagosian’s exhibition and sales sparked an ownership dispute between ABRF and the RDF and Gins’s estate over The Mechanism of Meaning, which resulted in a 2017 intellectual-property lawsuit (eventually dismissed). (There was also a 2019 employment lawsuit between the leadership of the two organizations, which stemmed from disagreements over how to manage the artists’ estates and work.)

In April 2021, after so many years of waffling, the Professors Group decided it was time to relist Bioscleave. “If the price is right, buyers will act,” D’Santos says. “This time, the sellers sat down and asked, ‘What would it take for this place to move?’ I said under $1 million will get attention, just because of the land value.”

“Here is a singular, rare masterwork — the only house [Arakawa & Gins] designed and built to test 50 years of research through this experimental, provocative laboratory,” the listing reads, emphasizing the pedigree. The price was also lowered again, to $975,000.

D’Santos’s hypothesis — that the land was worth more to someone than the house — was correct. “I had at least 100 inquiries,” he says. In 2018, it was mostly publications that wanted to talk to him; this time, buyers from England, France, Germany, New Zealand, Australia, and Syria got in touch. The Dutch actor from 2018 called again. The other actor, the one from L.A., made an offer this time. D’Santos also got bites from a museum that he won’t name that visited three times and asked about permits for public use. A bidding war was afoot. D’Santos got seven offers altogether, from a local real-estate agent who wanted to buy it for their children and grandchildren, developers planning a teardown, artists who wanted to open a residency for research into Arakawa & Gins’s work, and private buyers. (D’Santos — who lives in a colorful home of his own nearby — even considered buying the house for his kids.)

All were above the asking price, but not all the buyers were created equal. D’Santos presented the sellers with a dossier of everyone who submitted an offer, and they picked someone who shared their values. “The sellers and the buyer met in Manhattan for coffee and a slice of pizza, and they talked for two and a half to three hours,” D’Santos says. “They said, ‘These are the people we like very much and we think will be good stewards for the property, and we would like to move forward.’” D’Santos won’t name the buyer or the precise offer, of course, and the house is still listed on Zillow. But it is, after a road as bumpy as the floors and as colorful as the walls, finally in contract.